Blue Notes and Whole-tones: Reviewing Jazz at the Cooper Gallery

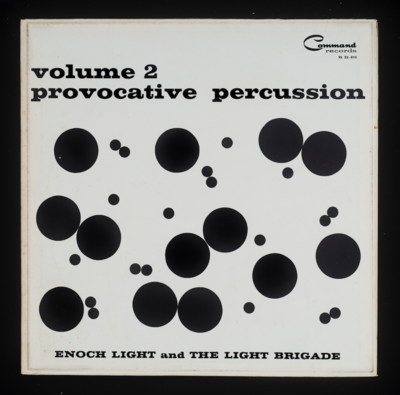

Joseph Albers. “Provocative Percussion, Vol. 2.” Enoch Light and the Light Brigade. 1960. Album. 12 x 12″ Courtesy of The Hutchins Center, Harvard University.

By Olivia J. Kiers

This spring in Harvard Square, Cambridge, MA, the Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African & African American Art is putting on a show-stopping performance with Art of Jazz: Form/Performance/Notes, an exhibition that delves as deep into jazz and art as it does into questions of jazz and black identity, jazz and myth, or jazz and place. While these juxtapositions exist in concert with each other, the Cooper Gallery offers less of an overriding statement as much as an intriguing series of questions.

The segmentation within Art of Jazz is to be expected from its subtitle: Form/Performance/Notes. This structuring follows from the organization of the exhibition across two locations: Form can be viewed at the Teaching Galleries of the Harvard Art Museums, while Performance (curated by Harvard’s Suzanne Blier and David Bindman) and Notes (curated by Cooper Gallery director Vera Grant) are housed in a series of intimate rooms at the Cooper Gallery. With delicate balance, the Cooper Gallery blends all of jazz’s oft-invoked narratives into that elusive dance between art and music. The visitor does not roam a white-walled gallery but instead embarks on a mysterious tour, invited into spaces that perform their own riffs connected by a corridor that strikes a blue note.

Hugh Bell. “Hot Jazz.” 1952. Gelatin Silver Print. 8.5 x 11″ Courtesy of the Hugh Bell Archive

There are not-to-be-missed aspects of this exhibition that, ironically, can be easily missed because they fit so well. Flanking the ramp that leads from Cullen Washington’s complex opening piece, Space Time, towards a shrine of evocative Hugh Bell photographs, is a wall of posters that advertise jazz’s hedonistic roots facing off with a self-assured row of album covers that reads like a timeline of mid-20th-century American art history, featuring designs by Josef Albers, Andy Warhol and Ben Shahn. Inside what looks like light fixtures hanging from the ceiling are in fact speakers softly playing selections from the albums on display, effectively pulling music off the shelf and bringing it to life for the viewer pausing to listen.

Whitfield Lovell. “After an Afternoon.” 2008. Radios with sound. 59 x 72 x 11″ Courtesy of the artist and D C Moore Gallery.

This incorporation of jazz music back into the gallery and into conversation with the art carries through to the final room, which houses pianist Jason Moran’s ghostly installation, STAGED: Three Deuces, a 52nd Street jazz club stage recreated. Revealing the constrained spaces in which Harlem musicians were expected to perform in Manhattan, STAGED: Three Deuces includes a sleek Steinway that is programmed to periodically play a haunting melody prerecorded by Moran. When playing, the music fills and overflows the space. The motion of the keys, however, signals the lack of a performer even more than when the music stops, invoking that tangled web of witness, place, history and performance that is touched upon throughout, as in Whitfield Lovell’s pile of antique radios in conversation with each other, titled After an Afternoon, Walter Davis’ collage explorations of jazz identity, or Christopher Myers’ mixed-media, New Orleans/Saigon phantasmagoria, Echo in the Bones. Together, these works craft a multivalenced vision of jazz, yet still acknowledge an incompleteness in the narratives they reference, allowing us, the audience, just enough of a long gaze to almost satisfy our questions before the performers turn away into history.

Art of Jazz: Form/Performance/Notes is on view through May 8.