George Shaw: The Yale Center for British Art Introduces a Contemporary Voice

By Susan Rand Brown

Fallen leaves litter the forest floor. A woman’s shawl, a swatch of royal blue cloth tilting upward, drapes on a barren limb. The Rude Screen, George Shaw’s title for this particular painting, suggests the push-pull of presence and absence that characterizes his work. The cloth with its deep shadows hints at something left behind; a ghostly haunt in this deserted spot. Autumn, the season of melancholy and desolation, seems made for this contemporary British painter, whose retrospective, George Shaw: A Corner of a Foreign Field, at the Yale Center for British Art (YCBA) through December 30, is creating a stir. Amy Meyers, YCBA’s director, describes Shaw’s art as “often provocative”—rooted within English (and European) landscape traditions while posing a challenge to its romanticized subject matter.

George Shaw, The Rude Screen, 2015–16, Humbrol enamel on canvas, 70 3/10 x 78″. Private Collection, courtesy of the artist and the Anthony Wilkinson Gallery, London. © George Shaw.

While a student at London’s Royal College of Art, Shaw (b. 1966) painted a cluster of row houses, focusing on the one with a green door—his boyhood home in Tile Hill. With this work, he found his calling (some say obsession). A Corner of a Foreign Field begins with this architectural portrait, No. 57, toned in tans and greens. The planned community of Tile Hill, nestled in lightly forested land near Coventry, was built to house the working class in the flourish of post-World War II’s utopian aspirations. Even today, as it falls into disrepair, Tile Hill remains Shaw’s literal and psychological terrain. A Corner of a Foreign Field, Shaw’s first solo exhibit in this country, traces the looping back and forth quality of his wistful visual poetry.

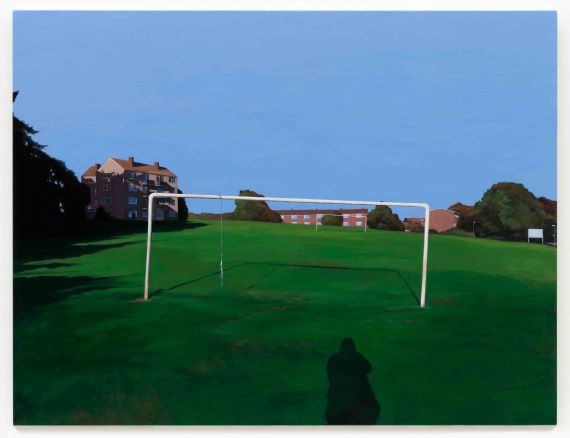

George Shaw, The Visitor, 2017, Humbrol enamel on canvas. Private Collection. © George Shaw.

Tile Hill is situated in the Forest of Arden, the setting for Shakespeare’s comedies of young love such as As You Like It. In contrast, Shaw’s own pastoral vision is similarly dark. With rare exceptions, there are no actual figures in his paintings. (In The Call of Nature (2015/6), he tweaks the conventions of landscape painting and poses himself, his back to the viewer, urinating against a tree, and in The Visitor (2017), the artist’s shadow lurks in the foreground as either a voyeur or spy.) As in The Rude Screen, human presence is stronger when implied.

George Shaw, Ash Wednesday: 7.00am, 2004–5, Humbrol enamel on board, 92 x 121 cm. Collection of Shacher Samuel, London. © George Shaw.

During a recent gallery walk-through covering over 70 paintings and numerous drawings—some monumental, clustered chronologically and thematically (there are ten themes, from “Recording a World” through “Paintings of Now”)—Shaw, a Turner Prize nominee, answered questions with a twinkle in his eye while leaving traces of mystery on the palette. As a boy Shaw took photographs while walking the nearby woodlands with his father, a factory worker who encouraged his son’s abilities. Today, photographs of Tile Hill and its surroundings form the basis for paintings that record the passage of time. Rather than paint with oils, signifier of “fine art” traditions, Shaw prefers Humbrol enamel paints, intended for hobbyists. Ironically, the glowing, romantic quality in his work, linking him with classicists like Titian (1488-1576) and other painters Shaw studied at the National Gallery, results from the enamel’s flat sheen. Both insider and outsider, Shaw casts an indelible tone.

Top Image: George Shaw, Scenes from The Passion: No. 57, 1996, Humbrol enamel on board, 43 x 53 cm. Royal College of Art, London. © George Shaw.