Then, Now and Tomorrow: An Exploration of Afrofuturism

A Conversation Across Mediums (Part 1)

Some say that pop music artist Prince lived it. Others say Octavia Butler was the early scribe of it. Artists like Sun Ra manifested it through sound. The “it” in question is Afrofuturism. You may have heard the phrase or you may have some idea of what it means. It is no surprise that this expansive yet hard-to-contain-within-a-specific-fixed-point term takes on different shades of meaning across New England. Maine has a number of Afrofuturist artists; the state’s Humanities Council was awarded $250,000 in 2022 to share Afrofutursim texts throughout the state. Maine is also credited with being home to an earlier Afrofuturist feminist text by Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins, Of One Blood published in 1902. This feature is in two parts, starting with conversations with artists Liz Rhaney, Arisa White, and Brian Evans on how they define the term and how they engage with their craft within Afrofuturism across the mediums of light, sound, writing, choreography, and movement. In part two, the conversation continues with Maine Humanities executive director, Samaa Abdurraqib, on how Afrofuturism created a bridge across all citizens of Maine.

According to the National African American History & Culture Museum–which has an exhibition dedicated to Afrofuturism through August 2024 –Afrofuturism “…expresses notions of Black identity, agency and freedom through art, creative works and activism that envision liberated futures for Black life.” And though the thirty-year-old term that was coined by Mark Dery in his 1993 “Black to the Future” essay, the enacting of Afrofuturism appears to be much older. This might depend on who you ask or how we’re defining what makes a piece of art fit within the genre of Afrofuturism.

For Rhaney, who engages in storytelling and archivism using light, video, and sound to “…sculpt a space into an experience shared by the audience,” Afrofuturism is about endless possibilities, specifically, “…it’s thinking about the possibilities of Black people in the past, the present and the future. It is not quite sci-fi, but futuristic speculative.” Rhaney shares another example about how she defines Afrofuturism using an episode from The Twilight Zone that aired in 1960. In “The Big Tall Wish,” a Black boxer reimagines the result of a fight he had long ago. This meant something else for Rhaney. “What struck me was that this story wasn’t about slavery. The story was about him, he was centered as the main character and that’s what Afrofuturism is. It is when Black folk are the main character of these curious and futuristic stories.”

Walking between the past, present, and future in terms of Black creativity and art also creates tension. Professional performer, choreographer, and teaching artist Brian Evans explores this tension in his definition of Afrofuturism. Of the term, he shares, “It is a beautiful, existential, indeterminate kind of space but it can also be a very practical way of approaching one’s art in one’s life. If I am on the pragmatic, cynical side, Afrofuturism, for me, is a reclaiming of sorts. It’s an attempt to create, especially in an artistic sense.” Evans adds that as a mixed-race individual, there is another dimension of the reclamation in that for him, the possibility of Afrofuturism is, “… sort of like an attempt for me to use a medium of art to create a space where every bit of me is seen and valued but not in any way in conversation to whiteness. It is thinking about art free from colonialism or free from a history of atrocity.”

To bring this definition home, Evans talked about seeing a recent performance by Latasha Barnes at a jazz festival; an act that included a five-piece band, a DJ, and ten dancers. Evans shares that on one hand there is a profound joy in this yet also profound sadness, stating, “We could have been doing that forever but it’s been systematically taken away from us. And so seeing these people on stage in their excellence is rare, because it’s been systemically erased or covered up or killed, murdered, deleted.” Evans is speaking to the ways that Black creatives and their work have needed to fight to survive and thrive within the systems of oppression.

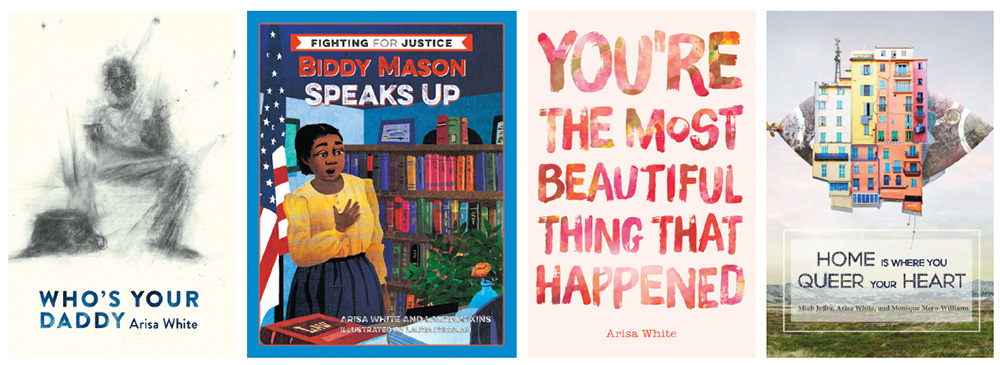

To walk between the past, present and future is its own challenge and one that strikes a chord with writer Arisa White, who is venturing into opera in her new work. For White, “…Afrofuturism has to do with a sense of imagining across time and space. It’s our ability to move between these kinds of temporal dimensions that we have created for our construction of time, to blur those lines that to go to the past, to go to the future, and even to bring the past in the future, to the present, in order for it to be lived in this more reflective, deeply emotional and spiritual way. It’s also kind of rooted in a Black feminist sort of thinking and visionary kind of way of orienting ourselves in the world where we can prefigure our futures, where we can imagine what is possible, based on the resources that we have now, and those resources being spirit, imagination, and intuition.”

Think about something you’ve encountered in this current moment, even if the term is unfamiliar. Think of Octavia Butler’s work—Kindred, or Parable of the Sower—or perhaps Alice Walker’s The Temple of My Familiar. Take another look at the 2020 television series Lovecraft Country which provides a visual aid for this walk between and betwixt past, present and future all while set within 1954. This navigation across time is accomplished in ways that range from the dialogue openly addressing the systems of racism to the appearance of other characters — from an Indigenous individual who was frozen for centuries to an enslaver who has to face what he has done to others who are able to break the boundaries and space and time to realize their full potential — to the inclusion of historic events like the murder of Emmett Till. To put it another way, pulling from Evans’s reference to Afrofuturism as an existential possibility: Why wouldn’t the forcibly (speaking to the historic reality of slavery) traveled Black body be used as the tool of redefining time across past, present and future as a superpower?

Speaking of Superpowers, What Were our Creatives

First Memories of Engaging in Creating?

Arisa White shares: “I didn’t even know I was necessarily exploring Afrofuturism in my writing because of the way in which I feel like it’s rooted in Black Women’s Ways of Knowing. It’s very Black to invoke the ancestors and to invoke those ancestors in a way that will fortify you for the present. Those superpowers of traditions, rituals, wisdoms, kitchen table knowledge, the literacy for the spiritual world…All of that felt like that is my inheritance to work with, my ability to borrow, recover, and reimagine.” For White, this is working through poetry which allows her to “…move across those temporal landscapes. And so, I’m working with language, the poetry of my mothers’, my grandmothers, my great-grandmothers, my Auntie’s, and the stories they have passed along. And the stories that they don’t even know they’ve passed along that I’m now picking up in my own embodiment.”

White shares that she often encounters something that feels familiar while working and she tells herself, “I am going to keep navigating and moving through this subject matter with the poem. The poem is sort of this spacecraft in a way, it is that vessel to help me pull things apart and put things together. What I realized is how to better use poetry, how to use whatever I learned in terms of the craft, rhythm, lineation, and how to tell stories through images. It’s using that more effectively, that makes it sort of Afrofuturistic.”

While White’s vessel is words and poetics, one of the entry points for Evans was the stage. “I don’t know if I had the conscious thoughts as a five, six or seven-year-old of the work I was doing.” At seven, Evans’s family moved to Minnesota. Shortly after, he and his family went from an all-Black space to an all-white space. He continues, “I remember growing up in Cleveland, there was art all around us. It was not necessarily talked about in a professional sense. In Minnesota, the art was not in the home, but was very external. I think about this in terms of academia and that is by design. When you think about technique and dance, you don’t think about West African or Hip-Hop, although those dances are just as technical. You tend to think about ballet or modern.” For Evans, the doing and the art was just a part of life, the art was situated within the everyday, not something separate or placed within the walls of a museum only to be experienced at a distance. He also remembers house parties as a little kid. “I think about those spaces and seeing my family dance and tell stories and tell jokes. Some part fiction, some part nonfiction. Again, in retrospect, when living in a system of oppression, you create multiplicities of layers of, of anything that you can to create an environment that is of love and joy, despite a world that would suggest that maybe you’re not capable of those feelings or things.” The clarity of creating and becoming was experienced in his role in The Wizard of Oz. He recalls, “I had four lines. I could bark, I could howl, I whimpered and then I had the biting of the witch. This was transformative for me as a seven-year-old because I could be anything on stage.”

For many creatives, it can be as clear as knowing that specific moment of where you were and when you knew you were called to make art. For some, there are variations on processes and realizations. This is no different for Rhaney who sculpts with light and sound: “It really was a process. I didn’t make the type of art I wanted to make until I got into my MFA program because I was worried about how am I going to pay the bills? How am I going to support myself with this? In doing that MFA, I was like, ‘I actually have the freedom to do what I want.’ And what I wanted

was to design experiences. I knew I wanted to use video. And that’s the imagination, right? If I really let my imagination go wild, I would be making these installations and these experiences.”

During her MFA experience, Rhaney asked herself, amidst her discovery of wanting to craft experiences, if she was going to make what she really wanted to make. The answer was simple. “I knew that the most reliable person to film was me, because I knew my schedule, when I was free. Making that video, [now titled Power], I just started talking about all the things that I want to talk about. Intersectionality. And how funky quantum mechanics is. For me, what I see Black and Brown women do on a daily basis is equally as wondrous as any of the things that Einstein is writing about in quantum mechanics. And after making several pieces, not just about me, but about particularly the Black and Brown folks around me, I was like, ‘Okay, what I’m doing is crafting these experiences, but each of these videos serves as some type of archive.” In hearing Rhaney’s approach of starting with herself as the central subject, one is reminded of the ways multi-disciplinary artist Carrie Mae Weems made this an imperative in her seminal 1990 photographic work, “Kitchen Table Series.” In this series, Weems herself is the subject. She was available and accessible, thus making herself and her life the art. This does not place Weems into the category of Afrofuturism per se, yet perhaps so in the way that both Weems and Rhaney positioned themselves at the center of their storytelling.

In all of these stories, we get the sense that to embed Afrofuturism in one’s work–either consciously or unconsciously–one is inevitably doing the traveling across blurred boundaries of past, present and future. Given this, how does place play a role? How does New England and more specifically, Maine, impact how each artist engages with Afrofuturism? These questions will be explored along with other illustrations of how Afrofuturism is unfolding across Maine through the work of the state’s Humanities Council.

BY SHANTA LEE