heART and Mind at Silvermine Arts Center

By: Emily R. Bass

Nobody is immune to struggle. Mental illnesses, grief and addiction can affect us all. Yet a stigma remains surrounding mental health, and discussions about emotions are often kept behind closed doors. Silvermine Arts Center’s winter exhibition heART and Mind (Through January 12, 2020) opens up these conversations, emphasizing the healing power of dealing with emotions within a community of people who care.

Such conversations about mental health are timely. Silvermine director Robin Jaffee Frank explains, “Why we did it at this particular time has to do with the alarming statistics throughout the U.S. and certainly in Connecticut about people facing mental health issues. It’s especially alarming when you hear about youth–the rates of suicide and severe depression are worsening, and that’s true in our community as well. Mental health is the main cause of hospitalizations in Connecticut.”

The artists in heART and Mind, who hail from all around the world, present their highly personal experiences in a way anybody can empathize with. The themes covered in this exhibition—addiction and recovery, trauma and healing, love and loss, isolation and connection, depression and hopefulness, and resilience—touch the lives of each and every one of us, whether we’ve experienced these challenges personally or care for someone struggling.

One such work is Susan Clinard’s mixed-media installation, Surviving Sexual Trauma Shedding Shelving Memory, which carries a particular weight in the context of the #MeToo movement. Central to the installation is the curved body of a figure, hunched over in hiding—the bent posture of someone desperate to not be observed. The figure is discordant and uncomfortable to look at, as if taking in this woman is an assault in itself. Shards of wood jut out of every surface like her fractured state of being, as this woman shelves and compartmentalizes her trauma in order to cope with the horror she’s experienced: hidden white tulle peeks out from cupboards and a pure white dress is torn to shreds, symbolizing a loss of youth and wide-eyed innocence. As much as the work rejects our gaze, visitors are drawn to the installation, many getting up close or even sitting on the ground to permeate the walls she’s erected. Despite the intentional discomfort, people are emotionally touched by this work and seek to touch this woman back, metaphorically extending a hand to an individual isolated by assault.

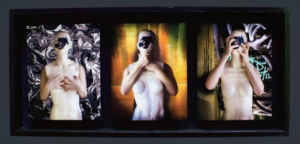

Barbara Ringer’s Dysmorphophobia is similarly concerned with discomfort from being observed and judged, its title derived from a disorder characterized by the feeling one’s body is inherently flawed and therefore warrants excessive measures to hide or fix it. Three mannequins clasp their faces and bodies, a futile attempt to cover a body with hands too small to conceal much of anything. Human arms reach around plastic bodies, symbolizing the uncanny dysmorphia that results from feeling one’s mind and body are divorced. It’s as if the subject’s physical form is trapping her true self, the person that exists in her mind but isn’t reflected in the mirror. While the societal expectations of beauty weigh especially on young women, an unhappiness with oneself and a desire for physical perfection are issues everyone faces at some point in life. Whether the concern is weight or aging, Dysmorphophobia painstakingly makes visible the pain many experience when comparing themselves against restrictive beauty standards.

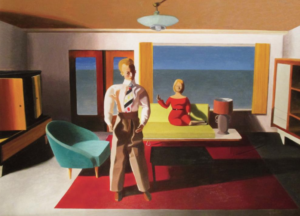

Kathy Osborn similarly draws attention to gender difference and its psychological effect on women in her miniature works, which depict domestic interiors of affluent couples set in the 1950s. Facing Away captures a husband and wife in the midst of a disagreement. The figures are still, pausing, yet one can imagine them exploding into conflict in the next frame. The ‘50s were a time when traditional gender roles were glorified: the “perfect” nuclear family was contingent upon a housewife’s adherence to gendered expectations—cleaning, cooking, caring for children. Osborn highlights the underlying problems this caused within romantic relationships as well as women’s own perception of self. She makes this wife’s unhappiness explicit, her mental and emotional isolation from her husband is tangible. Facing Away points to past power dynamics that now seem archaic in a 21st-century context, but patriarchy is not merely an issue of the past. By pointing out past imbalances, Osborn covertly critiques gender roles in contemporary society, as well.

Nash Hyon’s heartbreaking painting Swarming highlights a connection between the processes of grief and artmaking. Following her husband’s death from lung cancer, Hyon began painting as a meditative outlet to express her grief. His lungs are represented by a swarm of bees, connected by a spine of actual honeycomb. Made from encaustic (beeswax heated to use), the painting alludes to the cyclical nature of creation and destruction, of love and loss. “Bees make wax, that wax is turned into paint, and that paint creates a painting, with the artist being transformed by the process and the experience of loss,” wrote Hyon.

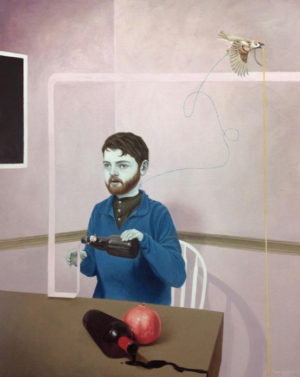

Alexander Churchill’s oil on canvas Self-Portrait as a Merry Toper depicts a struggle that is both deeply personal yet highly prevalent in New Canaan, as well as in other communities across the country: alcoholism and addiction. His scene seems to lie somewhere between a symbolic Dutch vanitas painting and a Surrealist dreamworld, plagued by a cold energy—or lack thereof. The figure dissociates from the world around him, caught up in his own state of mind as alcohol pours from his bottle and circles around the composition, symbolizing the addiction taking over his environment. According to Churchill, his paintings are concerned with “a series of indefinable emotional struggles,” stating that, “Honest self-assessment and reflection is key to the healing quality of art—which in turn lends power to positively change one’s relationship to the world and the people in it.”

The power to change one’s life and each other’s lives is central to the concept behind heART and Mind. “Too often in this society, prose and words are used to divide us, and these works of art were meant to bring us together and help us see that we share this common humanity…The exhibition is about things that we all share as we journey through life: getting to know ourselves better, accepting ourselves and engaging and embracing each other in a more authentic way. Ultimately, the exhibition is about the resilience of the human spirit,” says Frank.