Interview: C. Ondine Chavoya

by Bonnie Barrett Stretch

C. Ondine Chavoya is Associate Professor of Art and Latino/a Studies at Williams College. He is co-curator with Rita Gonzalez, Associate Curator of Contemporary Art at LACMA, of the exhibition Asco: Elite of the Obscure, at Williams College Museum of Art, through July 29, 2012. I spoke with him when I visited the College to review the show for the March-April, 2012 issue of Art New England.

Asco, Instant Mural, 1974, color photograph by Harry Gamboa

BBS: Asco survived as a vibrant transgressive group from 1972 to 1987—a period of fifteen years. Why I haven’t heard about it before?

Chavoya: That’s an excellent question. I think for a long time, their work didn’t seem to fit the narratives and paradigms we’d come to understand about conceptual art, political art, ethnic art, California art. It kind of played with all of them and disrupted all of them at the same time. These artists existed outside the commercial gallery networks in LA and elsewhere. They didn’t have the standard art school training so they weren’t connected with CalArts or UCLA or other art programs operating at the time. Also, both the commercial art world and the museums struggle with collaborative art groups; they tend to thrive on the cult of the singular artist. Asco was a different configuration.

BBS: It was a real collaborative. So how did this exhibition come to be? You and Rita Gonzalez, LACMA’s associate curator of contemporary art, were co-curators, and the show opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art last September.

Chavoya: The history of the show actually begins with the Williams College Museum of Art. I should say it begins with Rita and me and our long-term research and curatorial work, and our friendship [and interconnected interests] as undergraduates at UC Santa Cruz, later in graduate school, and on up to today. But the first museum to sponsor our proposal and to give it a space—intellectually and institutionally—was the Williams College Museum of Art.

Our original idea was to begin the show here and travel to Los Angeles. But the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time initiative invited us to align our show with that project of over sixty museum exhibitions focused on a full range of Los Angeles art from the post-war years. This was exactly the right context in which to present Asco’s history, so we switched the order of the sponsoring venues, opened at LACMA, and Asco became one of the real highlights of Pacific Standard Time.

BBS: In California, then, it was a big show in a big museum, with lots of clout. Here it is in a highly prestigious but small liberal arts college in the northwest corner of Massachusetts. It’s a magnificent show. But is this the only venue you will have on the East Coast?

Chavoya: We were originally partnered with a New York institution, but with the economic climate, their funding changed. We are still hoping for a New York venue. But Williams has a very rich if surprising history with Latino artists and particularly with Latino installation artists. The College has one of the very few programs of Latina/o Studies in a liberal arts college anywhere. And because Asco’s work is so interdisciplinary there’s a lot of engagement from professors and students in the theatre department, American Studies, Religion, Women and Gender and Sexuality Studies.

Also, when I taught at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and at RISD and introduced Asco and other Chicano artists from the Southwest, the excitement and interest was striking. That’s when I realized that the work could travel and translate and continue to inspire new work and new connections in contexts other than California.

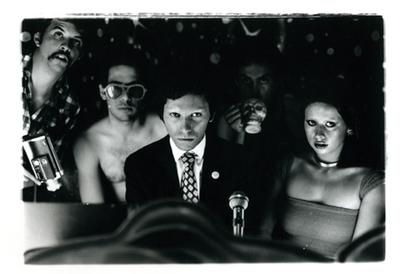

Asco, Asco Goes to the Universe, 1975. Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University.

BBS: Could you discuss briefly the impact that Asco had within the Chicano Art Movement and the Chicano community?

Chavoya: In the earliest days they were working to generate a response but they weren’t working to control that response. Their activities were happening on the street and were meant to be agitational, take people by surprise and generate a sense of “asco”—the Spanish word for nausea and disgust. That’s how they felt about segregation, poverty, about the schools they went to that had some of the highest dropout rates in the country. It was a response to the on-going death and destruction that was going on in Southeast Asia. One of their first events in East LA was Stations of the Cross—a mile-long procession carrying a huge cardboard cross on Christmas Eve along Whittier Boulevard, transforming the Mexican Catholic tradition of Las Posadas into a remembrance of the deaths occurring in Vietnam. Fortunately a photographer, Seymour Rosen, happened to capture the event on film.

On the other hand, their work was also very playful and irreverent. Part of it taps into that youthful, rebellious, do-it-yourself, don’t-ask-for-permission stance and style [they practiced]. What they did so well was recognize the arenas of culture that excluded them—the museum, mass media, political representation—and mark that exclusion, call attention to it, and create their own means and forums to generate a counter discourse. The whole idea of the No Movie was that they didn’t have access to Hollywood cinema, and they felt that the representations of Chicanos and Mexican Americans in the mass media were so stereotyped that they had to completely re-imagine what it would be like if they were in cinema. So they created this “cinema by other means.” They would say all they needed was “an idea and a dime.” And the dime was used to buy the postage stamps to send these things out through the conceptual and correspondence art networks, which is how they circulated their art and their ideas.

BBS: It’s all so ephemeral; it’s amazing how much of their work survived.

Chavoya: A surprising amount was saved because of the role of individuals and university libraries—Stanford University, UC Santa Barbara, UCLA’s Chicano Research Studies Center—and also the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art have archives of material donated by people who knew the Asco artists, art spaces that worked with them, and the artists themselves. So there have been concerted efforts at university research libraries to preserve and make this material available for future study.

BBS: Now that you’ve resurrected Asco, do you think it will have any influence on what’s happening in art today and in the future?

Chavoya: I think there’s a lot to be gleaned and learned from the way they engaged with difficult issues. There was a bold courage and playfulness to their work. I hope it will have an impact on how we think about art history and the potential for museums to do controversial programming. Questions of institutionalization, exclusion, navigation resonate deeply. These artists came together to create inspirational and aspiring work. They all continue to work and make art. So I hope that this renewed interest in their earlier work will increase the recognition of their current work as well.