Mary Bauermeister: The New York Decade

by Jenny Miller Sechler

How can anyone adequately describe the work of Mary Bauermeister? Her lens boxes, a series of drawings and scribbles arranged beneath an array of optical lenses, are enigmatic and astral. While most of the lenses draw the viewer closer to the densely packed detail, the occasional reversed lens reflects back, occluding what lies below. Bauermeister’s early environmental works, including canvases stacked with stone or streaked with sand, impose artificial order on natural objects while exposing the chaotic quality of the natural world. The current exhibit at Smith College Museum of Art—Mary Bauermeister: The New York Decade—documents the progression of Bauermeister’s artistic explorations and provides visitors an entrance into the artist’s world. The exhibit is worth multiple visits. Indeed, the complexity and fascination of Bauermeister’s work demands them.

Bauermeister was born in 1934 in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. As part of the first generation raised in Germany after World War II, history shaped her artistic sensibilities. In an interview with the Williamstown Art Conservation Center, Bauermeister explains: “We… did not trust anything our forefathers represented. Everything we were made to believe in had been proved to be an illusion.” This crisis of meaning led many German artists of her generation, to explore chaos and reject traditional art forms, as Bauermeister puts it, “to paint figures, landscapes, still lifes, at least to me and my closest artist friends, seemed ridiculous.”

Leaving school in 1957, Bauermeister moved to Cologne, where she became a forerunner of the fluxus movement and hosted concerts at her studio that were attended by luminaries such as John Cage. Her move to the United States was precipitated by her experience with Robert Rauschenberg’s Monogram, which she saw at an exhibit in Amsterdam. She remarked, “I was so flabbergasted by this piece, and I knew, where this is called art, I will and want to be!” Arriving in New York in 1962, Bauermeister spent a prolific decade in the city and was celebrated by fellow artists as well as critics.

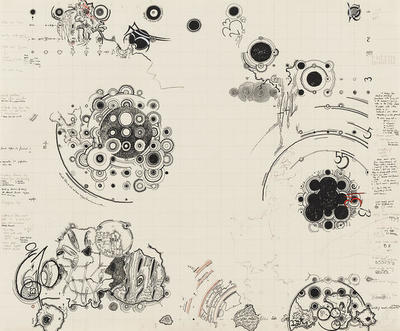

Entering the gallery at Smith, visitors are immediately greeted with a pen and ink drawing, Needless Needles, created in 1964. The drawing is riveting, and features multiple spheres, some overlapping each other, some partially framed by compass lines, suggesting the path of a planet in orbit, as well as patterns resembling those in nature, including tree rings and bark. Images of needles with roots sprouting from their points echo these arboreal themes. A series of notes written along the margins further engages the viewer into the world of the drawing.

Sand-Stein-Kugelgruppe, created in 1962 using found materials from the natural world, is another highlight of the exhibit. Consisting of seven different panels of varying size, the composition presents a fascinating combination of order and chance, starting with the very arrangement of the panels, which is left to the discretion of the curator. A large panel features more spheres that again echo planets in a solar system, while a smaller panel includes stacks of stones arranged meticulously from large to small, then aligned in rows. The arrangement of the stones reflects Bauermeister’s preoccupation with progressions and natural order. This interest entered her art through her use of specific imagery connecting one work to another. An example of this is Square Tree Commentary, an early lens box, which includes a photograph of a previous work.

As Bauermeister’s exploration of lens boxes continued, the boxes began to take on more structural elements, and her drawings and paintings started to incorporate bright colors. Bauermeister continued to explore order, chaos and mutability, while also introducing political themes into her work. Aest-H Etic Objection (1967 1969) provides an example of Bauermeister’s growth. The lens box has a hidden element: a raised barrier along the lower edge concealing a painting full of intriguing details, including two images from American culture—Mr. Clean and Joe Camel—meant to critique American consumerism. A large work—My Contribution to Light Art Is Dead, Serious Art—reflects the influence of her contemporaries. In this work, the lens box is eclipsed by its frame, which is arranged in curvilinear shapes reminiscent of Frank Stella.

Bauermeister returned to Germany in the early 1970s, and has been working primarily as a garden designer for private and public commissions. Bauermeister cites several reasons for her return, including a desire to raise her children in her home language, and for a connection to the German forest of her childhood. Bauermeister also describes a shift she observed in the New York art scene. “The early times…when the motive was art…had slowly changed into established movements,” she explains in the Williamstown Art Center interview. “The purity and innocence had vanished.” Whether one agrees or disagrees with this characterization, it is hard to argue against the innocence, or at least the sincerity, of Bauermeister’s own work.

Mary Bauermeister: The New York Decade will be on display at The Smith College Museum of Art through May 24, 2015

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Image Credit: Images courtesy of the Smith College Museum of Art.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Jenny Miller Sechler is an arts writer living in Northampton, Massachusetts, where she serves on the board of Northampton Arts, Inc.