War of the Roses

This fall, the Rose Art Museum will celebrate its fiftieth anniversary with an exhibition of works produced from 1961 to 1962 (its first academic year); a new renovation; and a sigh of relief that the hardest episode in its five-decade history is now behind it. If anniversaries are an opportunity to look forward and back—to commemorate history and imagine a future—the timing couldn’t be better: The Rose’s past, thorns and all, is clear; its way forward is another matter.

This fall, the Rose Art Museum will celebrate its fiftieth anniversary with an exhibition of works produced from 1961 to 1962 (its first academic year); a new renovation; and a sigh of relief that the hardest episode in its five-decade history is now behind it. If anniversaries are an opportunity to look forward and back—to commemorate history and imagine a future—the timing couldn’t be better: The Rose’s past, thorns and all, is clear; its way forward is another matter.

Founded in 1961, the Rose Art Museum began as a showcase for a collection of china donated to Brandeis University by Edward and Bertha Rose. By 1962, director Sam Hunter was hitting the New York galleries and artist studios, armed with a $50,000 donation by collectors Leon Mnuchin and Harriet Gevirtz-Mnuchin, who wanted to furnish the new museum with a contemporary art collection. Working with Mnuchin, and limiting purchases to $5,000 apiece, Hunter, a former MoMA curator, New York Times art critic, and acting director of the Minneapolis Institute of Art, selected twenty-one pieces by leading artists of the day that remain the heart—and the bread and butter—of the Rose’s collection: works by Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Jim Dine, Tom Wesselman, James Rosenquist, Adolph Gottlieb, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Morris Louis, and Andy Warhol, now collectively valued at more than $200 million.

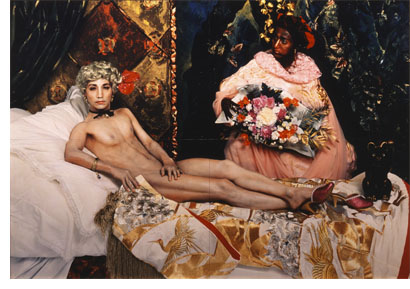

The museum maintained its toehold in the contemporary art community by focusing on socially conscious work by such artists as Judy Chicago, Ana Mendieta, Nan Goldin, Barry McGee, Zhang Huan, Alfredo Jaar, William Kentridge, and Christian Boltanski. It gave artists including Nam June Paik, Dana Schutz, Kiki Smith, and Frank Stella their debuts, and landed reviews in national art publications of record including Artforum and Art in America in the process.

But in January 2009, it looked like all that could come to an end when Brandeis president Jehuda Reinharz announced that the school would shutter the museum and sell off its collection of some 7,500 modern and contemporary works, valued at $350 million, to ease a budget deficit exacerbated by the economic downturn.

“The Rose is a jewel,” Reinharz said. “But for the most part it’s a hidden jewel. It does not have great foot traffic and most of the great works we have we are just not able to exhibit. We felt that at this point, given the recession and the financial crisis, we had no choice.”

The Brandeis, museum, and art-world communities swiftly mobilized against the move, and Reinharz backpedaled within days, first saying the school might just close the museum, but keep the art; then admitting he had “screwed up.” But the Rose, as it was, began to be dismantled nonetheless. By April, esteemed (and vocal) director Michael Rush had been let go, along with a sizeable portion of the staff. In July, several board members and major donors sued to prevent the school from selling off the collection, and the Rose entered a holding pattern, unsure of whether it would continue to exist, in what form, with what art, and under what leadership.

Now, almost three years later, the worst of the Rose crisis is behind it, with Reinharz out and his replacement, Frederick Lawrence, having settled with the Rose board members in June of this year, promising that “the Rose is and will remain a university art museum open to the public, and that Brandeis has no plan to sell artwork,” according to Brandeis.

The settlement marks a major turning point for the school and the museum—a chance to move forward. Although the news came as a relief to museum supporters, it also left many wondering just exactly what the resurrected Rose will look like.

Superficially, it will look updated, thanks to a $1.7 million renovation funded by a 2002 donation from former board member Gerald S. Fineberg, who, notably, had joined the lawsuit against Brandeis. When the Rose reopens in the fall, the entryway will be reconfigured with a new vestibule and reception desk; floors, ceilings, lighting, and the museum’s climate-control system will be replaced; and the museum’s pool, long love-hated by curators and administrators, will be gone.

Superficially, it will look updated, thanks to a $1.7 million renovation funded by a 2002 donation from former board member Gerald S. Fineberg, who, notably, had joined the lawsuit against Brandeis. When the Rose reopens in the fall, the entryway will be reconfigured with a new vestibule and reception desk; floors, ceilings, lighting, and the museum’s climate-control system will be replaced; and the museum’s pool, long love-hated by curators and administrators, will be gone.

Programmatically, much will still be up in the air. The day before the settlement was announced, I met for the first time with acting director Roy Dawes, a self-described “nuts-and-bolts” guy who was clearly chagrined at how little he was able to say about the museum’s future. A few weeks later, he was certainly more optimistic, but not much more informed. “We’re all still trying to wrap our arms around this thing,” he said. “We’re just trying to figure out, ‘Ok, now what do we do?’”

In the post-recession bad-news cycle, the Rose had become an easy symbol of the extremes to which the recession was pushing institutions. It was a worst-case scenario the culturati could rubberneck and “tsk-tsk” and be glad they weren’t involved with—the art-world equivalent of a murder investigation or lurid political sex scandal. In summer 2010, headlines flared again when Brandeis entered a relationship with Sotheby’s in which the auction house would help the school lease works from the collection for profit.

The Rose was no stranger to the cross. In the early 1990s, facing a drastic budget reduction from the university, Carl Belz, the Rose’s longest-running director, had also resorted to selling works. “They were going to take all the university support away from the museum,” Belz said in a phone interview, “and deaccessioning and building an endowment were the only way I knew how to save it.” In a move that also served to cement the Rose’s identity as a modern and contemporary museum, Belz decided to sell thirteen late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century works, including examples by Renoir, Degas, Bonnard, and Vuillard.

The American Association of Museum Directors—for which Belz was not eligible, as the Rose did not meet the minimum budget requirements—reacted much as it did in 2009, voting to sanction the museum. The Rose auctioned the works anyway, carefully divvying up the proceeds into separate endowment funds so that only those from works that had been donated to the school, not the museum itself, went toward operating costs, and the remainder went into acquisition funds, in accordance with AAMD standards. Sanctions were dropped, and the Rose was saved, able to move forward without university funding, relatively unscathed.

Though rarely mentioned during the Rose scandal of 2009, Belz’s decision inadvertently affected what would happen in its aftermath. Shortly after Reinharz’s announcement, the school formed the Future of the Rose Committee, a group of eleven representatives from the faculty, staff, Brandeis and Rose boards, student body, and museum. Central to the committee’s recommendations, released in September 2009, was that the museum must first and foremost serve Brandeis: “The driving idea behind our report is that the University take steps to better integrate the Rose Art Museum into the broader educational mission of the University.…In our view, the Rose, like many of its fellow university museums, has been oriented too much towards the art world, and not enough towards the academy.”

The report drew heavily from an early-1990s Andrew W. Mellon Foundation report that found that university museums had, thanks to the “professionalism” of museum and art history staff, become “divorced from the academic pursuits that defined their parent institutions.”

The report drew heavily from an early-1990s Andrew W. Mellon Foundation report that found that university museums had, thanks to the “professionalism” of museum and art history staff, become “divorced from the academic pursuits that defined their parent institutions.”

“Universities themselves bear some of the responsibility for the ‘mission drift,’” the Rose committee wrote, explaining that as external sources of support became available to museums, universities encouraged them to go after these sources and become more self-supporting. “In response, museums began to shift the balance of their efforts towards the sorts of activities that would appeal to their sponsor base (art patrons and the art world), and away from those that would advance the academic and instructional goals of the larger institution.”

To reverse this trend in the ’90s, the Mellon Foundation funded select universities to bring on staff dedicated to integrating their museums into academic life. Brandeis was not part of that program, but on the committee’s recommendation, it sought to replicate the initiative, hiring in 2010 a director of academic programs for the Rose, Dabney Hailey, who had been a curator at the Davis Museum at Wellesley College (which had received Mellon funding). The move can be seen as a well-meaning effort to better integrate the Rose into the school—and a successful one. In an interview, Hailey said she welcomed forty classes into the museum in the 2010–11 academic year, branching beyond the usual fine arts classes to involve disciplines such as business and peace and justice.

But for some watchers, the hire suggests a departure from the museum’s historical identity. “When I was there, we considered the museum to be a player in the arena of the contemporary arts, both regionally and nationally,” says Belz, who Reinharz pushed into early retirement in 1998, after twenty-four years at the helm. And, if the committee report is right, the university’s defunding of the museum in the early ’90s only pushed it in that direction. After Reinharz’s announcement, Belz says, “there was talk about how the museum was going to be a kind of teaching museum. That would be a very different kind of museum. It doesn’t necessarily mean it wouldn’t be a good museum or a valuable museum, but it would be, in a sense, more insular. ”

Some are more fatalistic. “The Rose as we knew it is dead,” says Francine Koslow Miller, a critic for Artforum and Art in America who has long reviewed Rose exhibitions and is releasing a book about the scandal in February, tentatively titled Cashing in on Culture: Betraying the Trust at the Rose Art Museum (Hol Books). The Rose served as a major hub for the local art scene, she says, and “I’m still feeling the effects of the death of the art community.”

The question now, says Belz, is “What kind of museum is this going to be?” Will it be a teaching museum catering to students and faculty, with, as the committee recommended in its report, more exhibitions featuring the permanent collection, as well as faculty and maybe even student work? Or will it be the contemporary art world player of the past fifty years?

And which would most benefit the university? When Brandeis threatened to close the Rose in 2009, it wasn’t because of the cost of running the museum, which is supported mostly by donors. It was because Reinharz saw in the Rose a valuable “jewel” that the university could do without. The jewel is still there (as is the controversial relationship with Sotheby’s, though not yet acted upon), but maybe the hope of the Future of the Rose Committee, and donors like Gerald Fineberg, is that by shining up the building and bringing more students into it, Brandeis will find it invaluable after all.

But wouldn’t the Rose wither without outside, or art world, support? After all, it was the perseverance of a few wealthy donors—one who put $2.5 million on the line—that brought about the 2009 crisis’s official resolution.

Whatever direction Brandeis chooses, the recovery will take time. “The lawsuit and the threatened sale have gone away, but that

doesn’t mean we’re up to full speed by any means,” says Dawes. The museum’s member, fundraising, and acquisitions programs have all been on hold since early 2009; a director and a curator need to be hired; and relationships and trust need to be slowly rebuilt. “It’s like turning around a supertanker. When it comes to a dead stop, it takes a while to get the engines going and get things working again.”

The anniversary, officially being celebrated October 27, with an exhibition heavily drawing from the Gevirtz-Mnuchin collection that first gave the Rose its name, is a good place to start. “I was going to certainly put together a fiftieth anniversary exhibition, but I wasn’t using the word celebrate, which I am now definitely embracing,” says Dawes. “It’s going to be a hell of a show.”

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Kris Wilton is a freelance writer and editor based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her writing has appeared in Modern Painters, Art+Auction, ARTnews, Emerging Photographer, Slate, and the Village Voice, among other publications.