Exploding Native Inevitable

This Critically Important Exhibition at Bates College Museum of Art Educates, Awakens, and Delights

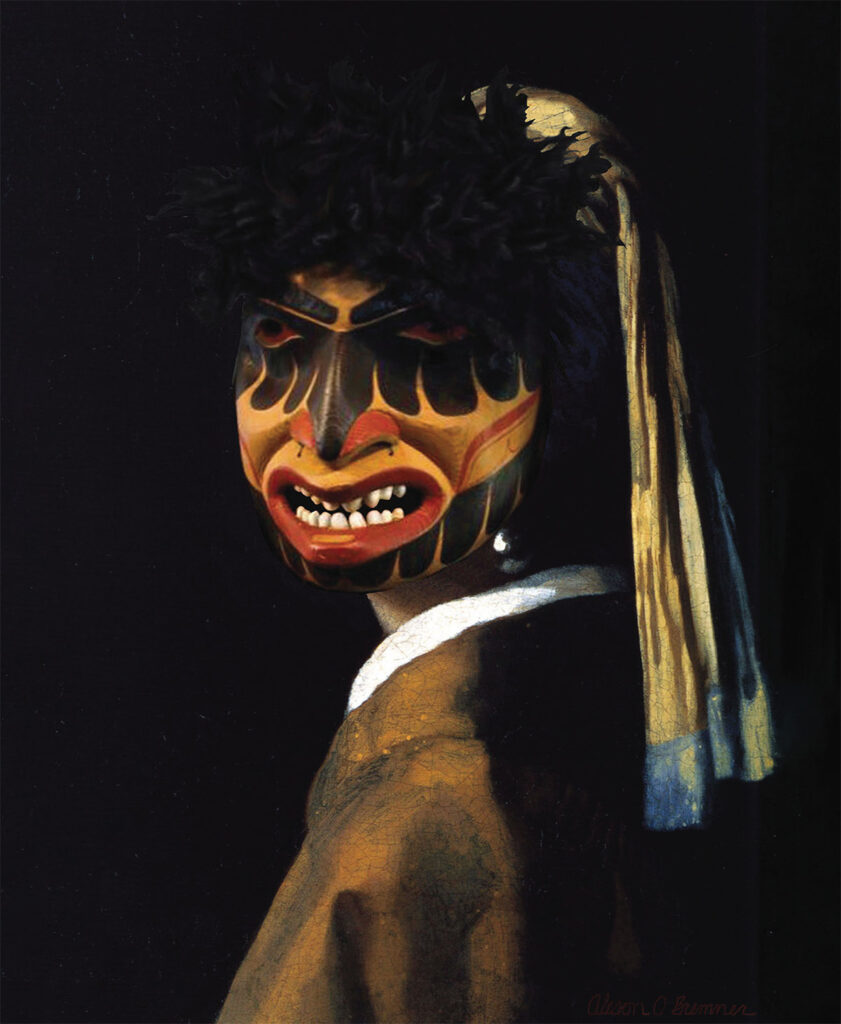

In her digital photograph Wat’sa with Pearl Earring, 2014, Alison Bremner (Tlingit) gives Vermeer’s famous painting a stunning makeover. She replaces the young woman’s face with that of Wat’sa, which means land otter in Sm’álgyax, the dialect of the Tsimshian language spoken in northwestern British Columbia and southeastern Alaska. As Bremner has explained, these shape-shifting creatures “would take the form of a beautiful woman and appear to unsuspecting men to steal them away.”

Bremner’s is a startling appropriation, turning the placid visage of the Dutch girl into a fierce-looking mask-like face. According to the artist, the image “examines the exclusion of Northwest Coast art from the canon of ‘great art’ in mainstream art history.”

Bremner is one of twelve artists and two collaboratives represented in “Exploding Native Inevitable” (through March 4, 2024) at the Bates College Museum of Art, an exhibition whose mission is to highlight some of the most provocative and engaging Indigenous art being made today. Co-curators, artist Brad Kahlhamer and museum director Dan Mills, have gathered an extraordinary group of artists from across the U.S. working in a wide variety of media and materials. Inclusion is the operative word for this head-turning show.

Many of the featured artists take on the status quo in direct manner. For example, Jaque Fragua (Jemez Pueblo), from Albuquerque, likes to use public spaces to send messages. Sometimes he commandeers abandoned billboards on reservations, as in Sacred Peaks, 2014, where he painted the word “sacred” on a sign fronting a range of mountains. A graffitist at heart and at times in practice, Fragua refers to these works as “public interventions,” another way of saying “in your face.”

In her hand-modeled stoneware sculptures Raven Halfmoon (Caddo Nation), who resides in Norman, Oklahoma, seeks, in her words, “to break the mold of the romanticized Native American stereotype and to simply say: We are still here and we are powerful.” Halfmoon’s Dush toh Dancing, 2022, does just that, presenting the head of a Caddo woman, her neck and part of her face daubed with a bright red glaze. The title refers to the traditional hair ornament worn during dances.

Like Halfmoon, Norman Akers (Osage Nation) draws on his tribal heritage as a source for material. His use of narrative, he writes, “acts as a continuation of the Native American storytelling tradition” in which “ancestral tribal stories and sayings have served to explain the world in which we lived.”

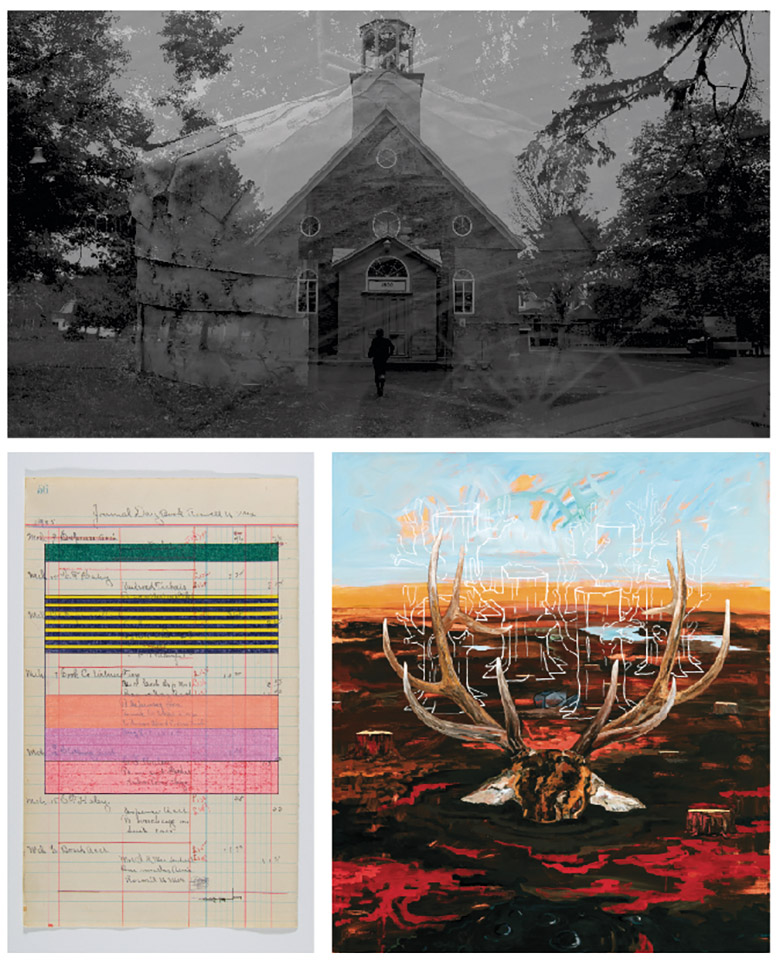

Akers’ large (78 by 68 inches) oil on canvas Watchful Eye, 2023, serves as a kind of elegy to a way of life. The head of a twelve-point elk appears to sink into a brown and red morass, its antlers reaching up into a decimated landscape of tree stumps. The Lawrence, Kansas-based artist’s charged image reflects the environmental devastation brought on by fossil fuels and other climate-changing forces.

An alumna of the Institute of American Indian Art, Nizhonniya Austin (Diné/Tlingit), who lives in Santa Fe, describes her painting style as “almost completely unguided and unplanned.” The lyrical abstraction in her 40 by 40 inch acrylic Forgive the Future, 2021, brings to mind the paintings of Arshile Gorky (1904–1948)—instinctual and full of energy.

“Exploding Native Inevitable” features a number of videos, including several by artist and composer Elisa Harkins (Muscogee/Creek Nation), who focuses on performance “and the body” in her work. A resident of the Muscogee Reservation in Oklahoma, Harkins blends elements of traditional Native culture with contemporary music, dance and clothing.

In Fake Part 2, 2015, Harkins, sporting dark glasses, calls the Indian Arts and Crafts Board to confess that she is making fake or inauthentic art. With the number “1-888-ART-FAKE” running along the bottom of the screen, she leaves messages listing the ways in which she has broken the law, including wearing a Navajo wedding bonnet during one of her performances. The video is at once humorous and unsettling as she deals with a pre-recorded answering service.

The other artists in the show, Sky Hopinka (Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin/Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians), Terran Last Gun (Piikani/Blackfeet), Fox Maxy (Mesa Grande Band of Mission Indians and Payómkawichum), New Red Order (Adam Khalil and Zack Khalil, Ojibway, and Jackson Polys, Tlingit), Mali Obomsawin (Abenaki First Nation) and Lokotah Sanborn (Penobscot), Sarah Rowe (Lakota, Ponca), Duane Slick (Meskwaki/Sauk and Fox Tribe of the Mississippi in Iowa), and Tyrell Tapaha (Diné), add to the rich cultural dialogue through storytelling videos, “ledger art,” defiance, playfulness, trickster figures, and fiber. Obomsawin might speak for all of them when she states, “We’re telling powerful stories now, and you would benefit by engaging with them now.”

The exhibition title derives from Andy Warhol’s “Exploding Plastic Inevitable,” a series of performances, concerts, and film screenings organized by the Pop artist in 1966–1967. Inspired by this multimedia extravaganza, the museum has organized a series of cross-campus events and programs—an explosion, if you will, of local, regional, and national performers, filmmakers, writers, and other Indigenous artists “from a land we now call America.”

In a separate concurrent show, “Nomadic Studio, Maine Camp,” curator Kahlhamer shows selections from his sketchbooks and related work. His on-the-spot drawings from “yonderings” across the country and the globe from the early 2000s to 2022 offer often fantastic visions of landscapes, figures, and creatures rendered in watercolor and ink.

This exhibition coincides with an ongoing debate over the call for sovereignty by Maine’s tribes. While they won a statewide referendum in November to reinsert a section of the state’s constitution that concerns treaty obligations that had been removed in 1875, their attempts to achieve the right to self-determination have been thwarted. A visit to this exhibition might help various legislators better understand what it means to be Native in a difficult land.