Leaving a Trace

One artist’s commitment to the voice, legacy and unifying power of quilt making.

Jennifer Mancuso

Photography by Christine Breslin

Secret messages were hidden in quilts, helping enslaved people communicate and navigate with each other as they traveled through the Underground Railroad. An enslaved woman, Harriet Powers, has two story quilts known to have survived. Although not indigenous to them, African American crafters are credited in advancing quilt making with colors and designs. Originally, quilts were made for function, an extra layer on a bed or to stop a draft on the floor. Often, scraps of old fabric came in pre-packed bags with the buyer never knowing what she was getting in terms of color or texture. Ed Johnetta Miller remembers this of her grandmother. “Mother,” as she was called, would buy woolen suits and coats at thrift stores and patch them together. “The quilts that my relatives made were functional quilts, they had a purpose.” They were not family heirlooms nor labors of love at that time, yet quilts marked a place in Black history just the same.

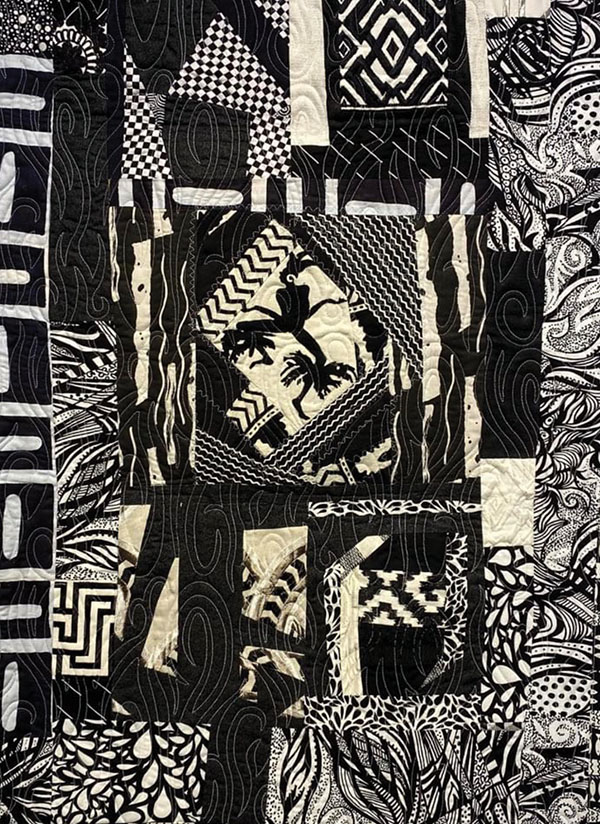

Miller has carried the tradition of her ancestors and risen to unimaginable heights with her art. One piece, Rites of Passage II, is part of the permanent collection at the Renwick Gallery in the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., while another hangs in Nelson Mandela’s National Museum in Cape Town, South Africa. Her many accolades include the Governor’s Art Award and the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Arts’ first President’s Award. The artist has also been featured on HGTV’s Simply Quilts. Currently, Miller is showing 25 new pieces at Art for the Soul Gallery in Springfield, MA.

Born in Spartanburg, SC, Miller did not start her career as a quilter, but as a fiber artist. When Dr. Carolyn Mazloomi, founder of the Women of Color Quilters Network and a strong advocate for the preservation of quilts in the African American community, encouraged Miller to submit a piece to a show at Wilberforth University in Ohio, a new medium, one with familial history, was presented to Miller. The show was entitled Uncommon Beauty in Common Objects and the fledgling quilter designed a coat with different fabrics that she had collected from all over the world. She would lay two fabrics together where the cultures had experienced some tension and in between, she would lay a solid piece, “with the hopes that we can come together.” At the opening, the coat was flying on fish wire. The piece Many Cultures Collided then traveled for two years and went on to become Miller’s first piece to hang in the Smithsonian.

Through the years, quilting has evolved from a utilitarian form into an artform. Among Black artists, quilting has had a place with each changing political tide. The Freedom Quilting Bee Cooperative formed in 1965 became a way for women in Rehoboth, AL to earn an income. The celebrated Gee’s Bend Quilters Collective is not far away geographically. With the Black Power Movement came a need to connect with heritage and preserve pieces of African American culture. Quilts were another voice with which to document history, to tell a story, and Miller is an extraordinary storyteller.

Through her quilting, Miller is also an activist. Her piece, I Have Known Injustice All My Life was featured in the New York Times. Within the work there are images of raised hands, Black figures, and the Statue of Liberty. Squares of text read, “I Can’t Breathe, Justice for George, Don’t Shoot, and Black Lives Matter.” The border fabric is filled with skulls while the red throughout symbolizes blood. Her most powerful social justice quilt is entitled We Have a Story. “If we did not have this filmed, people would not believe us,” Miller says of recorded violence at the hands of the police. Another equality piece of Miller’s depicts the Greensboro sit-ins of 1960 and uses a photo transfer technique onto the fabric. The work was shown at The Mariposa Museum in Oak Bluffs, MA in 2019 and shortly after the opening the gallery director called to tell Miller someone wanted to speak to her. It was the widow of Ponce De Leon Tidwell, pictured in the photo protesting at the Woolworth counter.

Among the 25 new works, Miller’s favorite quilt, Shades and Colors for You, is part of the current Art for the Soul exhibition. It is also one of her larger pieces. The work originated from fabric given to her on her first trip to Ghana when she was invited to sit with a chief of a village. Miller was told it was impolite to turn down any kindness which is why she found herself drinking a warm stout beer early in the morning. Before the end of the visit, the chief offered her a material as a gift. “This is silk kente cloth, it is fraying and it is over 150 years old,” Miller remembers him saying. “I want you to take this cloth and make me proud.” Upon returning to the States, Miller designed the piece. The border of Shades and Colors is the kente cloth and it is her most publicized quilt. Miller is thankful the chief had a chance to see the completed work before he passed away. “If I had a choice, it would be that one that hangs in the Smithsonian,” she said.

Writing came to her late in life and Miller now combines the written word with her art, further propelling her storytelling with accompanying text for each piece. The artist is writing her second children’s book, the first The Short Moth was based on her grandfather. Her latest project was inspired by a seed sack pouch she found in his old trunk—a thin cotton material often used to make clothes, much like flour sacks. In collaboration with the Stowe-Day Foundation, Miller is spearheading a project to teach pouch making. “[There is a] significance of women, especially African American slaves, [who] would carry it under their apron,” Miller says of the pouches. In the fields, enslaved women would collect seeds, like cotton, so they could grow the crop on their own. With her seed sack project, Miller plans to make her nieces and nephews a pouch with a special embroidered message in hopes that a bit of her history will stay with them.

Miller equates a fabric’s origin with being another voice of the quilt, along with the hands that create the piece—both voices combining to ensure that the work, that the stories, survive generations. Traditionally made by women, quilting has a rich kinship in the community and Miller wants to pass that artform on to as many as possible. The artist continues to hold classes and visit senior centers so older people can document their histories. Miller teaches sustainability and uses recycled pieces whenever possible. She speaks of her fabric angel in Hartford, CT who works at the design center and instead of sending the samples to a landfill, the angel drops the fabrics off to Miller’s porch. She, in turn, shares it with her students and neighbors. Miller doesn’t waste anything. Another significant piece in her exhibition is dedicated to the men in her life and is made with the discarded ties of her friends and family. Composed of fabric from a loved one or an embroidered message, these quilts become historical documents. “They tell their story through the cloth.”