Rewriting History: Tracing Hip-Hop’s roots from Basquiat to Boston

In early 2020, a group of Boston scholars, artists, and community activists seeded a question that would have unforeseen reverberations, both for visual arts scholarship and the city at large. It centered around the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, known as the young Black artist who died of a drug overdose, his paintings selling in the millions as the lore around his short life morphed into the idea that he was a misunderstood genius–What could an exhibition about Basquiat and the origin of hip-hop in New York mean to Boston? The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston meant to set the record straight, and in the process, updated history—clarifying Basquiat’s and his peers’ significant and overlooked contributions to the art of their time, and as the vanguards of Hip-Hop culture.

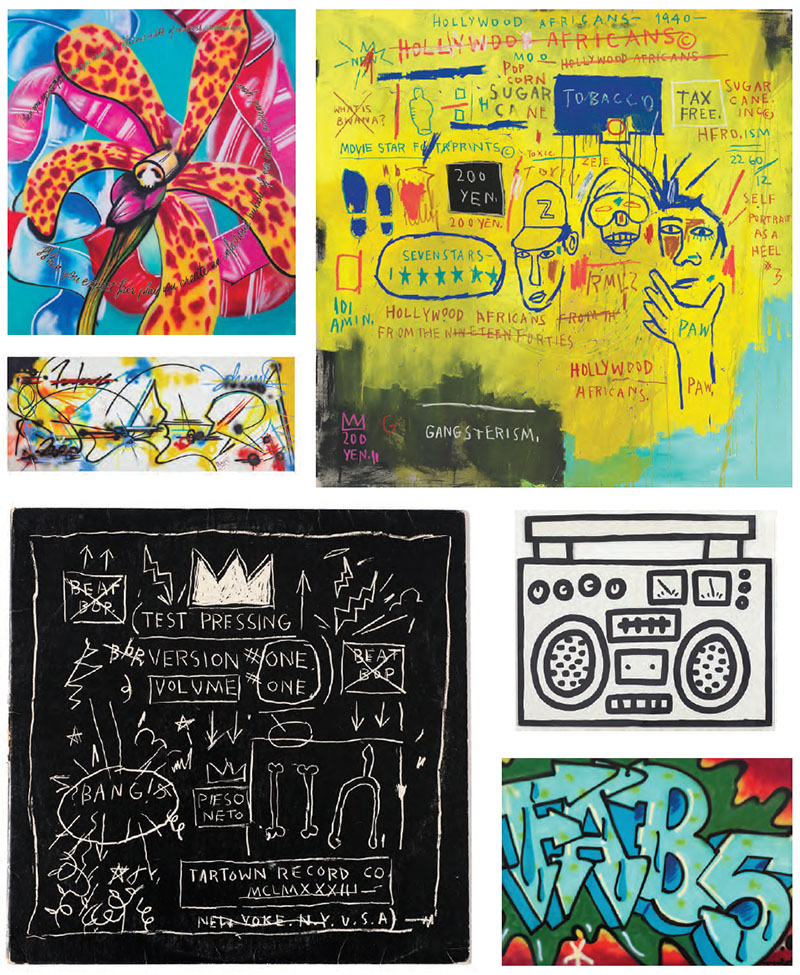

The resulting exhibition and catalogue, “Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation,” celebrate and correct the art history (and popular history) canon in their thoroughness, tracing back to the roots of a pivotal time in American contemporary fine and popular arts. “Writing the Future” features core artists in and around Basquiat’s orbit: A-One, ERO, Fab 5 Freddy, Futura, Keith Haring, Kool Koor, LA2, Lady Pink, Lee Quiñones, Rammellzee, and Toxic. These anti-establishment artists changed the course of contemporary art and popular culture—ushering in the Hip-Hop movement that began nearly 40 years ago and thrives today.

Near the end of the 1970s, New York City had undergone an economic collapse leaving the sprawling city, its boroughs and urban neighborhoods, bleak and barren. The Hip Hop movement was a call and response on the part of young artists from diverse backgrounds—particularly the Latinx and Black communities—to express themselves and reimagine the culture around them.

When you say those two words together, Hip-Hop,

it embodies the energy of the youth.

While most associate Hip-Hop culture with the streets of New York, Boston has played, and continues to play, an important role in its beginnings—Fab 5 Freddy and Lady Pink created a mural and debuted the film Wild Style in Coolidge Corner in 1983. Both are active today. Springing from the exhibition, the MFA’s first Black artists-in-residence, Rob Stull and Rob (Problak) Gibbs, continue the Hip-Hop story. While “Hip-Hop” was initially defined as a rap-inspired form of music originating in the South Bronx in the late 1970s, it quickly became a global movement that transcended art forms and infiltrated commercial culture. Hip-Hop culture, as it has come to be known, is multi-disciplinary—at its core are the four elements of turntabling, breakdancing, subway writing, and rapping.

Co-curated by Liz Munsell, The MFA’s Lorraine and Alan Bressler Curator of Contemporary Art, and Greg Tate, New York-based scholar, writer and musician, the exhibition was initially a focus on Basquiat. Munsell explains, “I thought I was getting into a Basquiat show at the very beginning and trying to offer a new perspective on this artist’s incredibly rich work and history, and bring something entirely new to it.” Yet the research revealed there was much more to the story. Basquiat had created a series of portraits of his contemporaries, fellow artists of color, who were also part of the post-graffiti movement. Together, this group of artists, Munsell says, intentionally transitioned their work from the streets to the galleries and into the predominantly white art world: “That’s why we define it as a movement in our history, because it’s a group of folks who were on a similar mission. And there are certain aesthetic commonalities as well—their interest in comic book culture, their bold color palette, the centrality of language and abstracting language through their own signature style.” These artists shared an interest in language, which was reflected in all that they marked and made: from subway cars to paintings on canvas, from found objects to sculpture. Hip-Hop showed up in fashion, film, and music—elements of scratching and sampling, rap, breakdancing and freestyling were often expressed and reinterpreted in the “scene” of the 80s.

Co-curator Greg Tate sees the show as a platform for another important course correction: “Jean-Michel had a Black community and a Black artist community. Because like Jimi Hendrix, he was kind of sold in media as someone who existed in a so-called white art world.” This was exacerbated by the fact that he was showing with artists like Andy Warhol, Francesco Clemente, and Julian Schnabel. As Tate says, from a distance, “it looks like this was his universe.” But in New York at that time, “the downtown cultural scene was really, in some ways, analogous to what you found in the South, during most of Jim Crow, which was that Black and white people and cultures were right on top of each other, always involved in kind of an intimate social exchange.”

The exhibition itself mimics the dynamism, cross-cultural expressionism, and over-the-top energy of the time, beginning with an installation quoting the subway cars which were the first “canvases” of the early graffiti writers. Organized into several sections, the exhibition includes paintings, sculpture, albums and album covers, film, and other objects and artifacts from the time period—including Basquiat’s lesser-known works. Blondie (Debbie Harry) appears larger-than-life on screen in a continuous loop; we see footage of Basquiat with a spray can; and in other galleries, white walls recall more traditional commercial galleries with paintings and sculpture on display. It’s a microcosm of the time. One of Rammellzee’s fantastical costumes, “Gash-O-Lear” (1989), looms large in the final gallery and speaks to the Afro-Futurist movement that sprung from the period. It’s a fitting conclusion—to end with a view to the future.

Basquiat (1960–1988) formed part of a group of peers who hung out, worked and “wrote” together, transforming objects, walls and canvases with their signature tags and fonts. This mark-making was in contrast to the cool minimalism and staid conceptualism that dominated the scene previously. Instead, these artists embraced language, noise, color, and sound, introducing an unabashed expressionism. Basquiat literally made his mark by writing on the walls outside of galleries, and then, once he had everyone’s attention, brought his art inside. His contemporaries followed suit. These efforts, Munsell says, “were fueled by a desire to see their multi-cultural identities and multi-lingual creative vocabularies represented by institutions that had seldom welcomed people who looked like them.”

Among them was feminist icon Lady Pink, one of a handful of early graffiti artists who successfully transitioned to the post-graffiti movement and beyond. “I was one of the very few female voices in the movement,” she says. Her early work mixed hard lines with soft forms, challenging ideas about “femininity” in artwork—whether she collaborated with Jenny Holzer to create paintings overlaid with Holzer’s text or fashioned entire murals with her fantastical architecture and flamboyant mark-making.

While “Writing the Future,” as Tate puts it, “looks like this gathering of the icons,” the exhibition’s related residency was out of another group of icons—present-day Black artists who are enriching Boston with their public art and community engagement. As Basquiat bridged Black and white culture in the 80s, Rob Stull and Rob (Problak) Gibbs are doing so today.

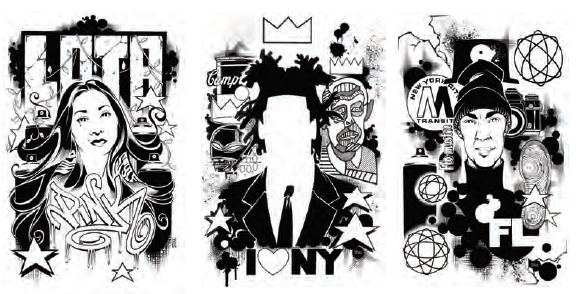

Created from an audience-building effort on the part of the museum, spearheaded by Makeeba McCreary, whom the MFA hired in 2019 as its first chief of learning and community engagement, community members from a variety of backgrounds were brought together—from Boston’s Hip-Hop community, the Black arts community, and other groups and individuals doing community-building work in the city. Shortly after this gathering, Stull and Gibbs were invited to be the MFA’s artists-in-residence. Roxbury-born Rob “Problak” Gibbs is co-founder of Artists for Humanity, a Boston not-for-profit, and a well-known muralist in the city with his iconic “Breathe Life” series. He collaborated with students from Madison Park Technical Vocational High School and Artists for Humanity on his latest “Breathe Life” mural, with its monumental girl inside a bubble, the neighboring mural walls populated with a joyous constellation of books and art flying from her backpack. (One of these books is a copy of the Writing the Future catalogue, Liz Munsell was delighted to note.) This nod to the MFA acknowledges the museum’s more dynamic role in community building. Stull, known for his work for Marvel and DC comics, responded to “Writing the Future” with six tribute drawings that are featured in the exhibition’s community response gallery, and also adorn the façade of the MFA entrance facing Huntington Ave. Five of the drawings pay homage to “Writing the Future” artists, while the sixth honors Gibbs. Tate acknowledges the alienation towards major institutions felt historically by Black Boston youth, “and for good reason,” he says. He views both the exhibition and the residency as important correctives. “I never expected to see a show like this at the MFA, or even in Boston, just because of the racial dynamics of it,” he says. The residency is an important element: from Stull’s portraits rendered in his iconic black-and-white style to Gibbs’ mural a short walk from the museum, in neighboring Roxbury. “These artists are making Boston part of the bigger picture,” Tate says.

As Stull puts it, “I think there is a lineage that connects us through generations that’s unique to this area… And we’re constantly looking out for each other’s endeavors.” But Boston hasn’t always been as open to street art as New York. “If I say I’m a graffiti writer, it already has a stigma on it,” Gibbs says, noting that while outside of the city, it was celebrated. He wanted to bring a version of that back to Boston, and considered the challenges “fuel to keep doing it.” Yet timing is everything. If this opportunity had come to fruition earlier, he says, “I might not have been able to lock down purposeful messaging.” Stull notes how ground-breaking it is to be commissioned together by the MFA: “We come from the same school of thought—which is Hip-Hop culture. It’s not rap music alone. It’s not graffiti alone. It’s Hip-Hop culture.” Stull connects with “Writing the Future” in another way: “I’m of that generation that was exposed to it in the early to mid-80s. So what it did for me was completely dominate my life, and my way of thinking, whether I was pursuing work in graphic design or advertising, or with a mainstream comic book industry, Hip-Hop was always there.” To this day, he says, “Hip-Hop is in everything I do, even in the classroom. And I know I speak for Rob [Gibbs] as well. Gibbs concurs: “When you say those two words together, Hip-Hop, it embodies the energy of the youth.” Now that the residency is in full swing, with works already created and speaking to audiences and communities, both artists see the entire effort—the exhibition and the residency—as just the beginning. Basquiat and his generation did it then, and Stull and Gibbs are doing it now—redefining the gatekeepers, opening up the gates.

Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Through May 16, 2021

mfa.org